How a Windsor Mother of Three

Became a Radio Legend

Story by Matthew St. Amand

Photography Courtesy Trombley Family Archives

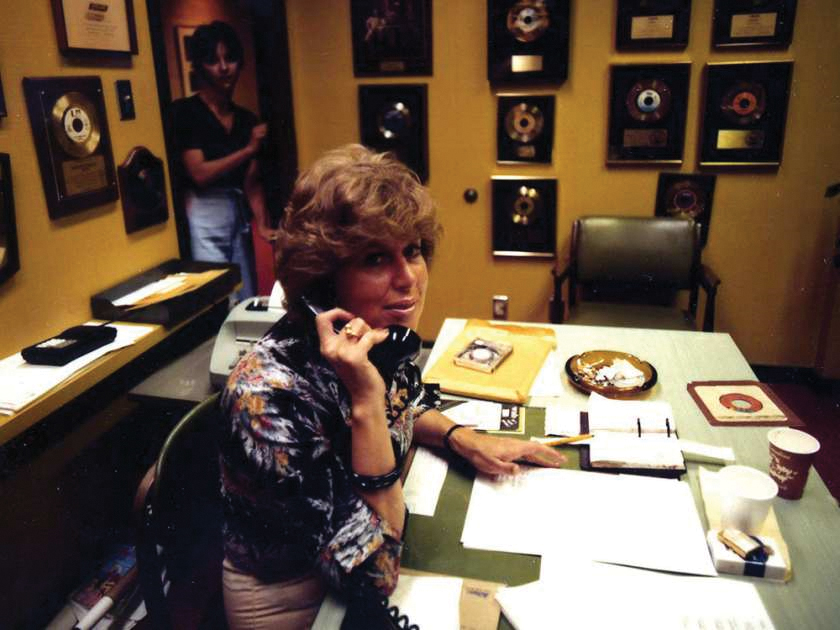

In a time when radio was king, she was queen. Rosalie Trombley was Music Director and one-person powerhouse at Windsor’s CKLW radio station from the late 1960s into the early 1980s—during a time when few women held positions of power in the broadcasting and recording industries. Rosalie passed away on November 23 and tributes from around the music industry have poured in, remembering her as a person with a singular talent for picking the hits.

Rosalie began at CKLW as a part-time switchboard operator on Labour Day Weekend 1963. Following a promotion to the music library, she ultimately served as Music Director from 1968 to 1984. In that role, Rosalie was known as “The Most Powerful Lady in Pop Music,” according to a 1971 Detroit Free Press headline, because her musical taste so strongly influenced what songs received air-time on the station.

“It must be remembered that CKLW was in the Top Five most listened-to radio stations in North America,” says Rosalie’s son, Tim Trombley, Director of Entertainment at Caesars Windsor. “Although it broadcast from Windsor, CKLW was known as a Detroit radio station. It was heard in dozens of American states.”

The songs Rosalie chose to play were not lucky guesses.

“Every Monday, she called between forty and fifty record retailers throughout Michigan and Ohio to see what was selling,” Tim continues. “She combined that with her own instincts for a hit record, which included monitoring CKLW’s request line. She tabulated the data and based her decisions on the results.”

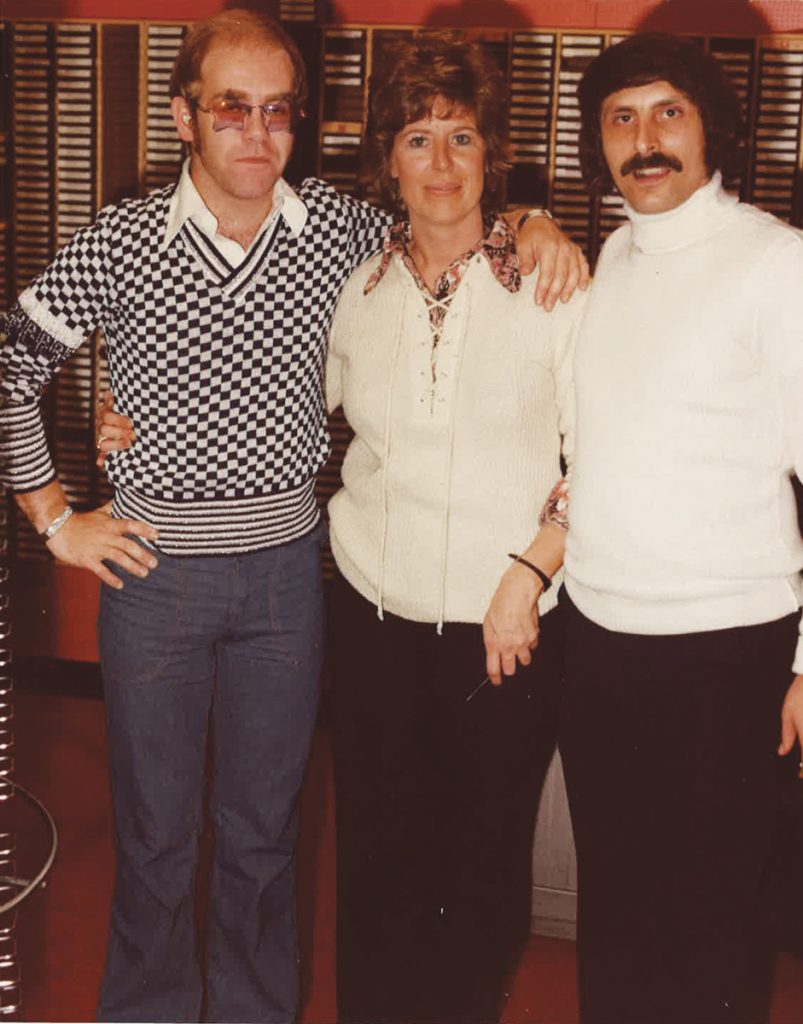

It’s clear, however, that Rosalie had a gift. After hearing an album cut by Elton John called “Bennie and the Jets,” played on Detroit soul station WJLB, Rosalie played the song on CKLW. The request lines lit up. The thing was, “Bennie and the Jets” was not scheduled to be a single from the album, Goodbye Yellow Brick Road. A song titled “Candle in the Wind” was the next single.

As she explains in Michael McNamara’s excellent documentary, Radio Revolution, about CKLW’s halcyon days, Rosalie received a telephone call from Elton John, who said to her: “I want you to tell me about ‘Benny and the Jets.’”

Rosalie asked Elton John if he ever had a top-selling record in the black market. He had not. She asked him: “Do you want a record that’s going to cross from pop to R&B?”

Rosalie continued: “And I’ll never forget what Elton John said to me: ‘Who am I to question what they want? If they want “Bennie and the Jets” then that’s what they’ll get.’”

After the single went gold, Elton John visited CKLW to present Rosalie with a gold single for “Bennie and the Jets.” He stuck around to DJ for the day as “EJ the DJ,” and even recorded a promo for the station.

The talent for picking hit songs must have been in the blood, because Rosalie’s eldest son, Tim, managed to do it, and so did her daughter, Diane.

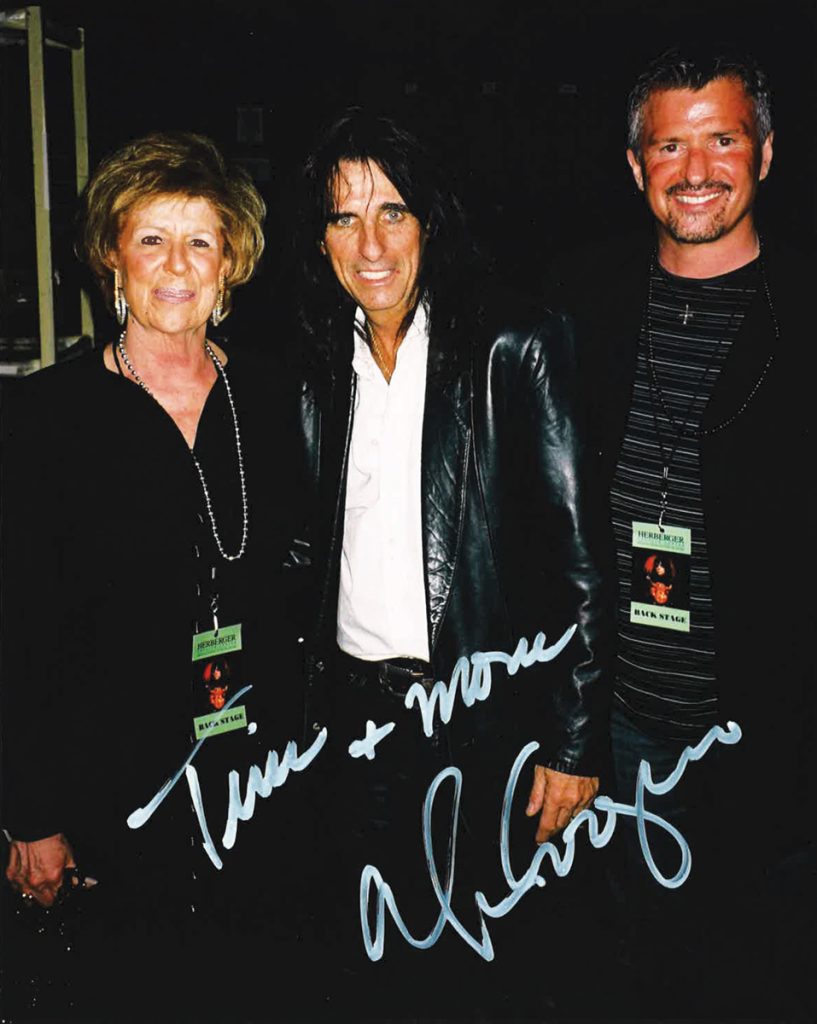

One of the perks of having a mom working at CKLW was Tim’s access to new records. He recalls his mother bringing home Alice Cooper’s, Love It to Death. Of all the tracks on the album, Tim was transfixed by the song “I’m Eighteen.” He told his mom and Rosalie played the song on CKLW. Alice Cooper, himself, states in Radio Revolution what exposure on CKLW meant to the band: “Next thing, it’s Number One. So, CKLW… we owe everything to them. That was the first time we felt viable. We always felt that [Rosalie] was part of our gang.”

Not to be outdone, Rosalie’s daughter Diane picked a hit for her favourite band at the time: Kiss. The song she played over and over on the band’s Destroyer album was a ballad called “Beth.” At Diane’s suggestion, Rosalie played the song on CKLW and its popularity exploded. Kiss subsequently visited CKLW and presented Diane with the gold single.

It was not only Rosalie’s uncanny ability to pick hits that contributed to her stature in the music industry, but also her utter incorruptibility.

“Record label reps knew she was a single mom, raising three kids,” Tim says, “and there were times they offered her money to play a record. She wouldn’t do it. If she didn’t believe in the song, she wouldn’t play it.”

Race and gender played no part in Rosalie’s decisions about what aired. Her son, Tim, notes that she had a great love of black music, saying: “We have a framed photograph of Marvin Gaye that he gave to our mom, and signed it: ‘To Rosalie, yours in peace and love, sincerely Marvin Gaye.’”

It was one thing to spin the feel-good hits of classic Motown, but as the 1960s gave way to the 1970s, artists became more socially conscious. None more than Marvin Gaye who recorded his landmark album What’s Goin’ On in 1971. Accepted as a timeless classic, now, Motown President, Berry Gordy, at the time, was reluctant to release the album, fearing it would harm Marvin Gaye’s commercial viability.

“The Motown promotion people gave it to Rosalie and she thought it was a hit,” Tim explains. “She understood the cultural shift that was happening in America, and in black music.”

Rosalie was also an invaluable supporter of Curtis Mayfield, the Stylistics, and Teddy Pendergrass, Dionne Warwick, Sammy Davis, Jr., as well as homegrown acts, such as the Supremes, the Temptations, the Four Top, Aretha Franklin, and Stevie Wonder.

Rosalie also supported fellow Canadians, hearing a hit in the Guess Who’s single “These Eyes,” and in Bachman Turner Overdrive’s “Takin’ Care of Business,” among other Canadian artists who benefited from the station’s reach.

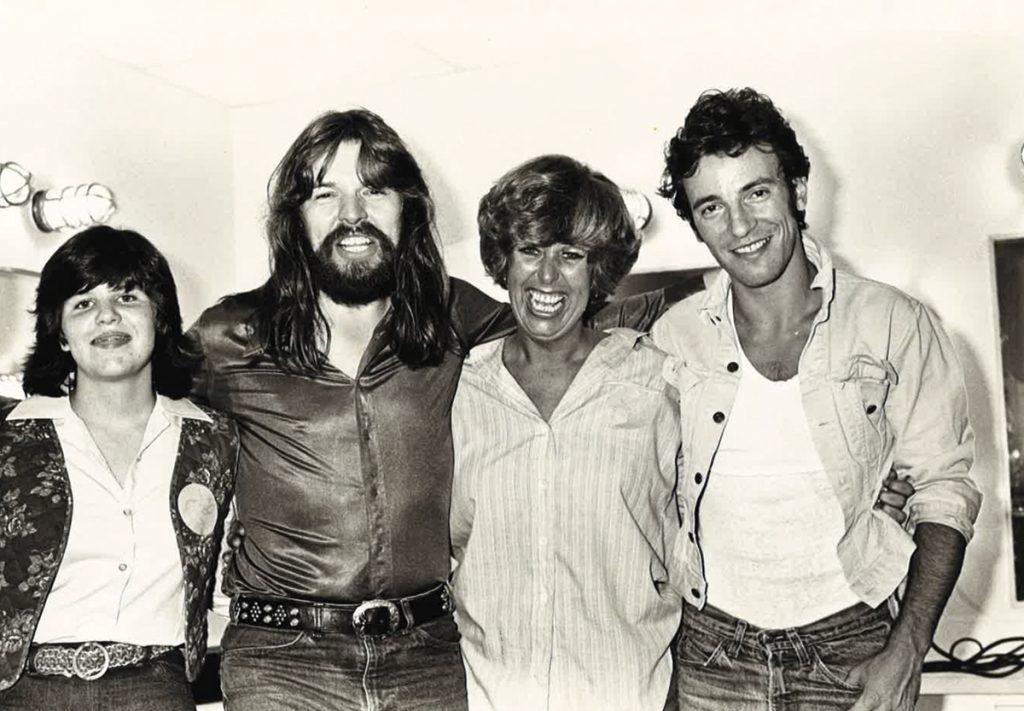

There was one Detroit musician for whom Rosalie had a particular fondness.

“She always had a love and affinity for Bob Seger,” says Tim. “CKLW was a catalyst in breaking Bob on a national level. Rosalie connected with his music, lyrically.”

Although she was a fan, that did not mean Seger’s music automatically made it to air on CKLW. As the New York Times obituary for Rosalie states: “Some of his new material came her way in the early 1970s, and she panned it. [Seger] sat down and wrote a song about her called ‘Rosalie’—a tribute to her importance, but with a sly, reproving undercurrent that they both laughed about later.”

The article quotes Rosalie as saying: “He was pissed off when he wrote that song about me. He told me!”

Rosalie insisted the song never be played on CKLW upon penalty of her walking out the door. They never played the song.

Another artist who credits Rosalie with making his career was Tony Orlando. Interviewed in Radio Revolution, Tony tells the story of Rosalie saying to him: “If your next record comes within the ballpark of a commercial record, a playable Top Forty record… I’ll give it consideration.”

His next record was “Tie a Yellow Ribbon Round the Ole Oak Tree,” the biggest hit of his career. “She was the first to put it on the air,” Tony remembers. “And the rest became history for me. We owe it to her. Rosalie Trombley made most people’s careers.” Tony went on to say that Rosalie had his vote for induction to the Rock ’n’ Roll Hall of Fame (though that honour has not yet happened).

Accolades for Rosalie’s talent often arrived at the CKLW offices in the form of flowers. On any given Monday morning, staff would arrive to find large bouquets at the front desk from people such as Elton John, the Rolling Stones, the Who, thanking Rosalie for playing their music at the radio station.

Rosalie’s fame and influence reached its zenith in 1979, when, on June 7, she was invited to the White House in Washington, D.C. The Black Music Association threw a party there and invited Rosalie to attend as thanks for her ongoing support. She attended the party and even met then American President Jimmy Carter.

All good things must come to an end, says the old proverb. By 1984, the radio landscape experienced such upheaval—with the rising popularity of FM stations, and listeners being lured away by MTV—that a mass lay-off occurred at CKLW to cut costs, affecting Rosalie, as well as many others.

Afterward, Rosalie managed to “keep on keeping on,” working for a time at WLTI-FM in Detroit, and then CKEY in Toronto.

In 2005, Radio Trailblazers, an organization that promotes women in Canadian radio, created the annual Rosalie Award, which recognizes women who have “blazed new trails in radio.” Rosalie Trombley was its first recipient.

In 2016, Rosalie received the Walt Grealis Special Achievement Award, a special Juno Award, recognizing her as “a true forerunner for women in radio between 1967 and 1993.”

Regardless of the honours, Rosalie always kept it real. As Tim explains: “What was so cool about my mom is that she loved her job. She was proud of what she did, but to her, the greatest accomplishment of her life was raising me, my brother Todd, and my sister Diane, as a single mother, in a little house in Riverside in Windsor.”

Add comment