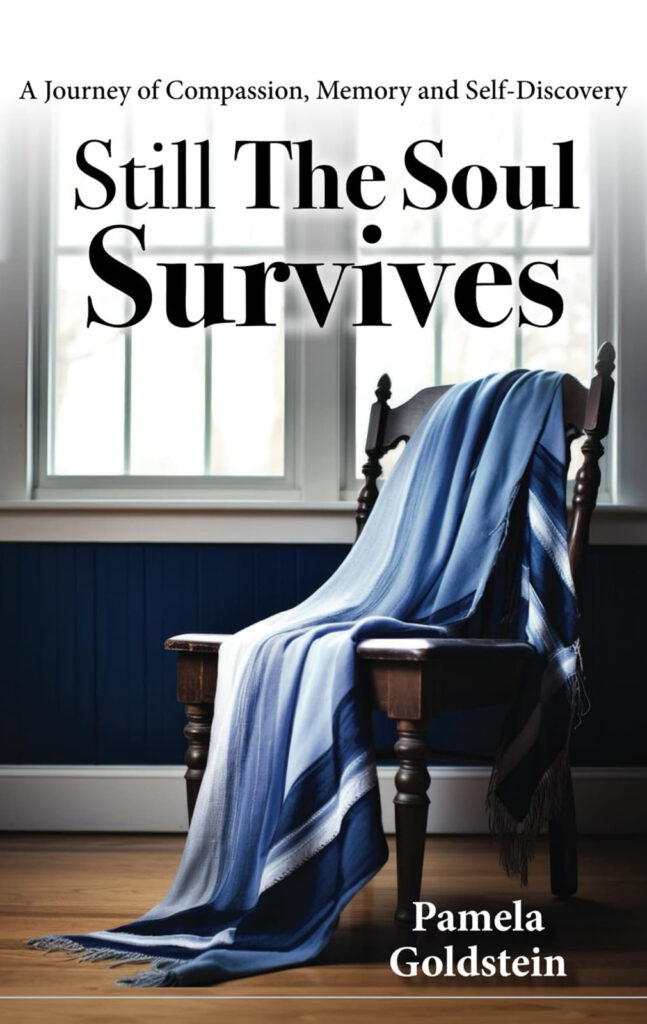

A Journey of Compassion,

Memory and Self-Discovery

Story by Alley L. Biniarz

Photography by John Liviero

The Holocaust happened nearly 100 years ago, yet the realities were ever present for the survivors and patients of Pamela Goldstein. As a young nurse through the early 70s, Pamela hadn’t learned much about the Holocaust. Little did she know that working in the hospital’s cancer unit would introduce her to survivors that would become like family and who would help her to uncover an identity that was long hidden from her. Now, after 20 years in the field, Pamela shares the survivors’ stories with the world along with her own memoir woven into the title Still the Soul Survives, A Journey of Compassion, Memory and Self-Discovery.

Pamela was 21 when she met Jacob Masinsky, the first Holocaust survivor she would encounter. As someone who lived in Riverside and went to school in the 60s, she was never taught about the Holocaust and was both horrified and taken by the stories of the war. “Our history teacher thought it was more important to learn about the Six Day War. He said that was local history in the making.”

She spent her time working in the cancer unit, listening to the stories of dozens of patients who were survivors and had developed cancer from experimental injections they received in concentration camps, especially Mauthausen and Auschwitz. Their conditions were chronic, which kept them in the ward for long periods of time. Pamela says that by the time she was in her mid 30s with kids of her own, she had become very good friends with many of them — including Ellie Lieber, the survivor who decided it should be Pamela that would document their stories.

At first, Pamela didn’t know why she was being chosen to write these stories. Why did the patients trust her with stories they’d never told before? On top of that, she wondered why she was so drawn to the Jewish religion and customs?

“Even before meeting my husband I was interested in converting.” She says. “After I began conversion classes I spoke to some of my relatives in Texas.” Her uncle confirmed that the family on the matriarch’s side was in fact Jewish. This revelation opened a world of memory for her.

She began to piece together how her maternal grandmother used to light candles on Fridays. She never said the prayers or did any of that, Pamela shares, so the grandkids didn’t think anything of it. In retrospect, Pamela can see that her grandmother was marking the beginning of Shabbat. The Rabbi, who Pamela took her conversion classes with, had wondered if the survivors sensed Pam’s heritage; Pamela did as well. “They were so insistent that I should write their stories. ‘Dollie’, who Ellie called me, ‘You’re the one who understands us, you are our friend.’”

When Pamela wrote the first iteration of the book she sat with a 300,000-word count. It wasn’t until a few years later when she was looking at the manuscript that she realized she had three different books on her hands. After pulling at some threads, she landed with the final copy we see now: a memoir about the survivors and how they affected her life, while piecing together her own discovery of her ancestry.

The newly published book follows Pamela as a young nurse moving through this personal journey and shows how truly dedicated she was to her patients. Over the 20 years Pamela listens to stories told for the first (and often only) time and holds them with reverence, knowing the sacred responsibility that is to be told such traumatic and tender stories. Through the years she becomes not only the keeper of their stories but an active participant in her patient’s lives as they continued about their days after the Holocaust.

Along with being tasked with writing this story, Pamela was asked to perform another sacred rite for her patients called the Tahara alongside a friend and social worker, Debbie. This is where the book begins, with the two of them performing this Tahara for Ellie, a rite that prepares her body for burial.

Neither of them knew what the process entailed and had gone to seek the help of Rabbis prior to the first Tahara to understand the depth of this ritual act of purification. They would need to follow strict procedures which includes the recitation of prayers and psalms, the washing of the body, and making sure the body and soul left the world cleansed by this act. It was a big undertaking and one that Pamela didn’t take lightly.

“It was an incredibly difficult thing for me to do but they all decided we were their only friends. We used to have tea with them, we met with them twice a month, and we were their family when they didn’t have one. That, plus with everything that happened to their bodies in the past, they didn’t want a stranger to touch their bodies,” Pamela explains. “A lot of these feelings are minimized in the book. Feelings of ‘holy cow, how am I going to do this?’ I left that part out because it’s not resolved. I’ve performed over 80 Taharas during the timeframe and I’m still not over it.”

Reliving these memories during the writing of the book was the hardest part of the process, Pamela shares. “I was a nurse for 20 years! Nurses don’t feel. You’re taught to maintain control and compartmentalize. Now here I was being asked to break through the barriers to explain how I felt. It was very difficult to relive the horrible things over and over. With every edit you’re reliving it again.”

But Pamela was driven by the belief that this is what she was meant to do. This was an important story that she was entrusted with and she needed to tell it the right way. What Pamela realized as she got to know her patients was that they became adamant about people having basic civil rights. The survivors knew the importance of freedom and would write letters in protest or go over to Detroit and march with groups. Pamela knew this was another chance for her to speak up. She couldn’t fall into “the drop of silence”, as one of her survivors put it. She couldn’t stay quiet about the atrocities she’d heard about; she needed to do her part and say something and to teach what she wasn’t taught.

“To look at the world today, so many people are apathetic and think they won’t make a difference because they’re one person. What I’ve learned from the Holocaust survivors is that you have to take up other people’s voices; the ones who have fallen or who can’t speak up for themselves. That’s your job in a democracy: to stand up and say this is wrong.”

With that, Pamela leaves us with this story. One of truth and liberation, of healing and belonging and one of hope that people will be more open-minded and stand up with one another.

Still The Soul Survives is available locally at Biblioasis, Indigo, Chapters or on Amazon.

Add comment