Amherstburg Author’s Quest For Meaning

Story by Ron Stang

Photography by Brendon Cloutier

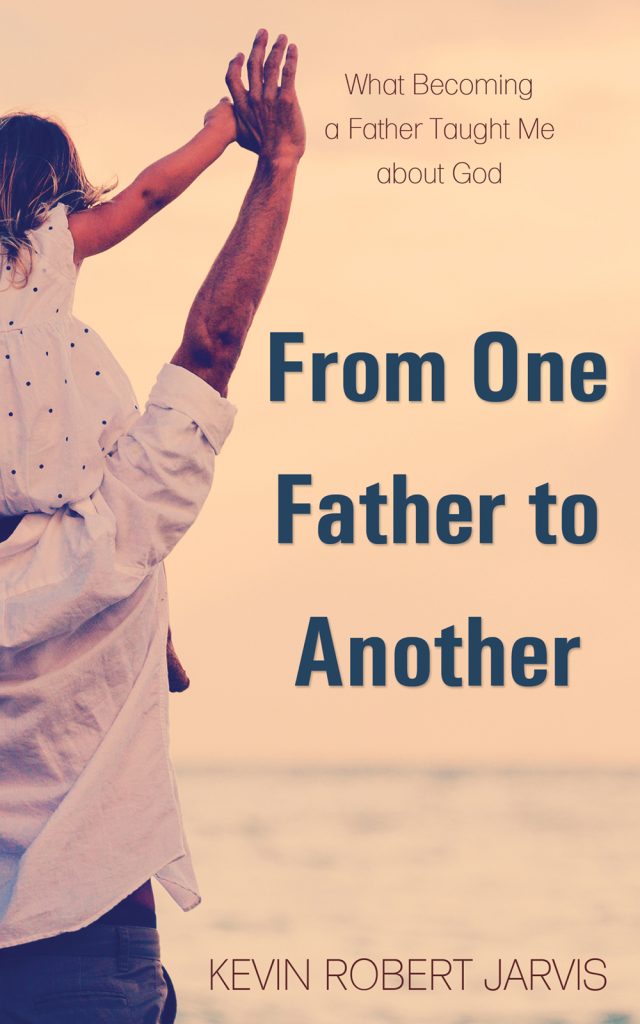

From One Father to Another is local author Kevin Robert Jarvis’s attempt to answer a series of religious—and broadly speaking, life—questions with a wide scope including fatherhood, family, the nature of life and the role of faith in it.

If you’ve ever wondered about the seeming contradictions and unanswerable questions about good and evil, why bad things happen to good people, why conflict and strife exist in the world, and yet why happiness and morality can still prevail, you might want to peek inside the covers of Jarvis’s book. (From One Father to Another, What Becoming a Father Taught Me about God, 152 pages, Word Alive Press; available through Amazon, $15.83).

Jarvis, 42, grew up and lives in Amherstburg with his wife Jessica and their three children, Owen, Kara and Luke. The names are important because he refers to them constantly in the book, using personal anecdotes from his family together with analogies and metaphors to come to grips with some of the Big Questions.

Jarvis also has a strong faith background, first as a teen participant at Amherstburg’s House of Shalom Youth Centre and later studying theology and pastoral ministry at Windsor’s Assumption University. He currently works as a law enforcement Special Constable.

As the book title implies, From One Father to Another is not only an effort by Jarvis to understand his place in the world but to share his questions and insights with other families, in particular fathers, who may have some of the same questions as he has had as they raise their families.

At the end of each chapter there are questions designed to have the reader reflect and probe deeper into the issues Jarvis has brought up and how they might apply to their own lives. Jarvis says he was surprised by how this “process of inquiry” led himself to a deeper understanding of spiritual matters.

Jarvis grew up in a broken home and didn’t discover religion until his teen years. But getting married and raising a family has been the key to further developing his spirituality. As he says, “Jesus used sheep, coins and wheat to explain God’s truths…why couldn’t God use my own children and my experience of being a father to teach me?”

Well, to be quite specific about it, anyone even a little bit familiar with Christianity will notice the metaphor right away. After all, the entire religious faith is based on the concept of “God the Father.” Personally, Jarvis says, fatherhood “has given me a glimpse” into the spiritual realm.

In more than a couple of dozen short chapters, Jarvis delves into many of the questions religious and even non-religious people have long asked and which underly everyday life. Like why does life go on in an often-calamitous world, if everything is preordained how do we have free will and do our prayers get answered?

And throughout, Jarvis refers to everyday episodes in his family, especially his interactions with his three children, as micro examples of how God works.

Jarvis’s questions and answers can be remarkably simple and will likely have readers nodding in agreement. For example, “If we are willing to ask God why he would choose to create us to live in a broken world so full of pain and suffering then must we not also ask ourselves why we choose to do the very same thing by having kids of our own?”

There’s also the old conundrum of free will, an “impenetrable problem,” Jarvis agrees. If God is all knowing how can human beings do whatever they want? The author explains by saying he also gives his children a certain amount of freedom but obviously he can’t be “attached at the hip” to them, especially as they grow older. Yes, as a father he can instill moral values but it’s up to them to carry those out. And so, in the bigger picture, God is also trying to prevent evil through our conscience. “But just as our children can ignore our warnings and promptings, we can do the same for God’s quiet – yet stern – voice in our conscience.”

Are we created in God’s image? No, Jarvis thinks, at least not in the anthropomorphic or looking “in the mirror” sense. But “just as my children” can take on what he hopes are his best traits “we also emulate and reflect qualities and attributes of God.”

And, no, just because we pray doesn’t mean we’ll necessarily get what we ask for. But, reflects the author, is that the point of prayer? By example, Jarvis talks of Christmas gifts his kids got and how they quickly tired of them. Or even after he himself obtained long sought goals or possessions he soon became “bored” with his new acquisitions. He calls it the “moving goalpost” syndrome. The answer to his children’s disappointment was simply to be there or show his “presence” whether through play or understanding. And so, “we can choose to be in (God’s) presence and build relationship or go off in search of something more.”

Kids ask the darndest – and most penetrating questions. One of Jarvis’s children wanted to know where God was and why He couldn’t be seen. This was tough to answer until Jarvis thought of the game Hide and Seek, though humorously admitting “no metaphor is perfect” so long as they “lead us to understanding.” In the game his kids couldn’t find him but there were “signs of my existence everywhere” such as pictures of him and his woodwork and guitars. As per St. Paul, he quotes, God is understood “by what was made.”

The author also takes on atheists. Answering the charge of a supreme being as only a “psychological projection” or because of a believer’s culture and upbringing, the same could be charged in reverse for non-believers. Jarvis argues that coming to terms with spirituality is more complex, for example relying on intellect, cognition and emotion. “The fact that some people believe God exists while others don’t in no way changes whether he exists or not.”

Should we be concerned about how “successful” we are in life? Jarvis ponders the question, particularly considering celebrity culture and society’s emphasis on material living. One of his children wants to be an artist and he “was struck” that he didn’t have a preference about what any of them should do. If anything, he wants them to grow up to be people of good moral character. Similarly, “perhaps God cares more that I am a general labourer of my own soul than that I gain world success.”

Add comment