The Story of one Essex County

Family Living With Dementia

Story by Matthew St. Amand

Memory is a mundane mystery. When it functions, we barely notice its monumental role in our daily lives. When memory breaks down, however, life itself seems to come off its moorings.

In the case of my aunt Michelle St. Amand, my uncle Don observes: “The kids noticed first. Anne-Marie said: ‘There’s something wrong with Mom,’ and I thought: ‘Really?’ It all happened so gradually.”

“At first, I noticed my mom searching for words when speaking,” my cousin Anne-Marie St. Amand recalls. “And I thought: ‘OK, she’s bilingual, maybe she’s trying to think of the French word…’ Then, around 2016, she stopped driving. I took her to doctors’ appointments, and she’d ask me to go in with her.”

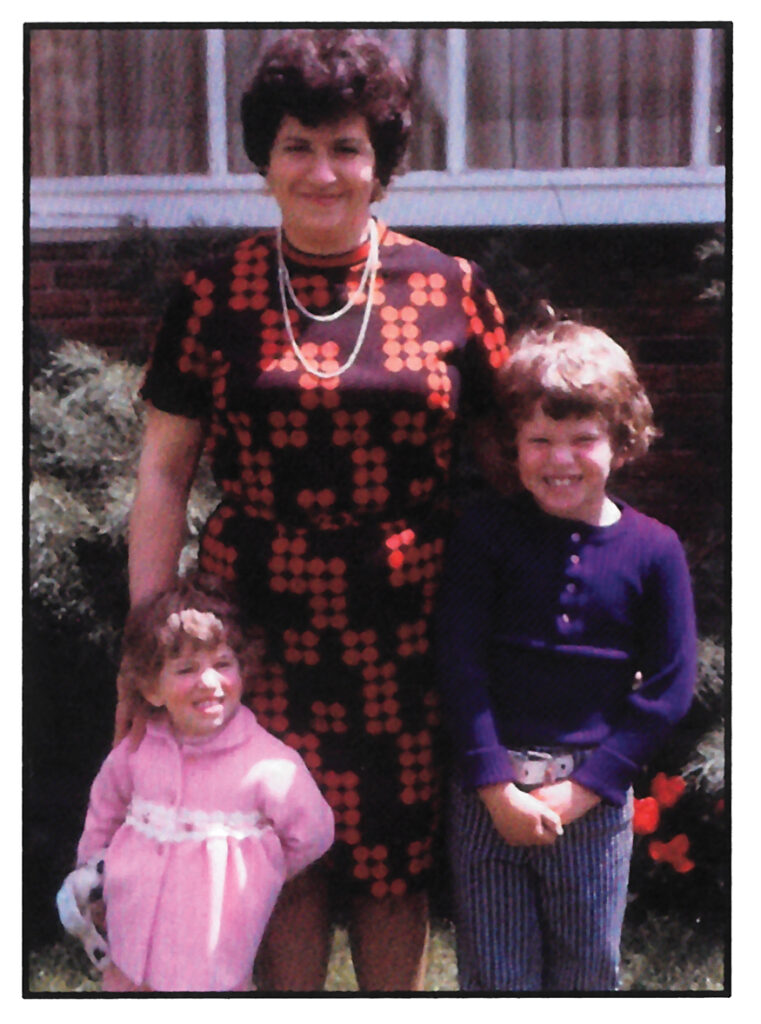

Michelle could no longer remember what was said during these appointments, which was a telling sign. In 1960, she graduated from Hotel Dieu Hospital School of Nursing. It wasn’t long before she was thrown into the horror and trauma of the profession: in October of that year, a gas leak explosion destroyed the Metropolitan store on Ouellette Avenue, killing ten people and injuring one hundred more. Michelle was among the medical personnel who tended to the victims, many with horrific burns.

That chapter of her career ended when Michelle was pregnant with her first child, David.

After David’s birth, Michelle returned to nursing at Riverview Hospital. Her time there ended when she was expecting Anne-Marie who was born in 1971.

In the extended St. Amand family, Michelle was the go-to person for medical advice. So, in recent years when she could not recall details from her own medical appointments, it was more than a momentary lapse of memory.

“Pieces of that person slowly disappear,” my cousin David St. Amand observes. Residing in Toronto since the late 1980s, he visits home regularly and witnessed his mother’s struggle in sharper, starker terms.

“Each visit, I notice something is different,” he says. “The last time, Mom couldn’t string her words together.”

Then, the cruelest aspect of dementia asserted itself: by slow degrees, Michelle no longer recognized her family.

“I was expecting it,” David says. “I told myself: ‘Don’t cry! She’s still your mom.’ What I do now is walk in and say ‘Hi, it’s David,’ and she says, ‘Hi David,’ but doesn’t understand who I am. You have to put your emotions away. It has nothing to do with me or how I’m feeling. It’s not her. It’s her mind. She’s still my mom.”

“Sadness and grief losing that connection I had with my mom as her daughter,” is how Anne-Marie describes the experience. “The way I see things now is that love remembers all. Although there are days mom recognizes me as Anne-Marie, she may think I’m her little sister. All that matters is the connection, knowing that she’s loved.”

“The hardest part is when the PSWs leave,” Don says. “There is no conversation.”

The St. Amands worked through their emotions and began the arduous process of getting help for Michelle.

“Mom was assessed by a nurse practitioner through the Geriatric Assessment Program,” David says. “Then COVID shut everything down and they closed Mom’s case. We called the Alzheimer Society, and they helped us navigate this. They couldn’t provide any services until mom underwent an assessment by someone through Home and Community Care Support Services or the Local Health Integration Network. Then an occupational therapist assessed her to determine how much help she needed. And that’s when we got the personal support workers coming to the house.”

In retrospect, the process appears streamlined, but it required innumerable phone calls, months of waiting, and wearying uncertainty.

After attending online Alzheimer’s “webinars” offered to family members with loved ones living with dementia, Anne-Marie suggested that Don try one, too.

“It was helpful hearing what other people are going through,” Don says. “We learned that you have to be calm. People with dementia get agitated easily.”

“You need many different strategies in your toolbox,” Anne-Marie says. “If mom doesn’t want to get up and go to the table for lunch, I’ll say: ‘Why don’t you stand up so I can see how tall you are?’ That’s working.”

One day when Don went to help Michelle in the bathroom, she said to him: “You can’t come in here! This is the woman’s bathroom!”

Memory is the keel that helps us maneuver through time. Without it, we are adrift. With Michelle, there is only now. Sometimes she thinks Anne-Marie is her sister, other times that Don is her father.

“I took some pictures of Mom sitting in her chair surrounded by her siblings,” Anne-Marie says. “Each photo shows Mom looking at one sister, then another sister, and then her brother, as if trying to work out the connection.”

Times when Michelle asks where her parents or siblings are, Don and David and Anne-Marie have learned to say: “They’re not here right now,” rather than that they have passed away.

Following the pandemic, Don took Michelle to The Memory Café hosted by the Alzheimer Society.

“She got up on her own and was chatting with people, speaking French,” he recalls. “She had a really good time. It was at the Ojibway Nature Center—a beautiful setting.”

After taking an online seminar about the need for care givers to look after themselves, Anne-Marie suggested that her dad needed a life too.

“So, I asked my friends Joe and Bernie if they wanted to go out on Friday afternoons,” Don says. “While the PSW is here, we go out for coffee. We go look at the bridge being built…”

On a recent visit to see uncle Don and aunt Michelle, I marveled at how placid she seemed. Four days before Don’s eighty-eighth birthday in May, Michelle turned eighty-six years of age and she looks very well; healthy, alert. When she heard my last name is St. Amand, she said: “Really?” Otherwise, the few times she spoke, she said “What?” or “Who?” whenever Don or I looked at her as we conversed. At one point Michelle said: “I don’t know…”

“What?” Don said to her, smiling. “You don’t know why you ever married me?” He laughed and kissed her.

This year marks their fifty-ninth wedding anniversary.

Dementia does not discriminate. The experience is as individual as the people who live with it. One thing is certain: there is hope and there are resources available. The place to start finding answers to questions is the Alzheimer Society www.alzheimer.ca/windsoressex/en.

I have the distinct pleasure of meeting the St Amand family, in late 2022, working along side Don and Michelle has been a great experience.

I always feel welcomed and highly respected while delivering care to Michelle and her husband Don. They both make me smile daily!! -Jaclyn, PSW/OTA/PTA